The practice of medicine has changed enormously in just the last few years. While the upcoming implementation of the Affordable Care Act promises even further—and more dramatic—change, one topic which has received little popular attention is the question of exactly who provides medical services. Throughout medicine, physicians (i.e., those with MD or DO degrees) are being replaced by others, whenever possible, in an attempt to cut costs and improve access to care.

The practice of medicine has changed enormously in just the last few years. While the upcoming implementation of the Affordable Care Act promises even further—and more dramatic—change, one topic which has received little popular attention is the question of exactly who provides medical services. Throughout medicine, physicians (i.e., those with MD or DO degrees) are being replaced by others, whenever possible, in an attempt to cut costs and improve access to care.

In psychiatry, non-physicians have long been a part of the treatment landscape. Most commonly today, psychiatrists focus on “medication management” while psychologists, psychotherapists, and others perform “talk therapy.” But even the med management jobs—the traditional domain of psychiatrists, with their extensive medical training—are gradually being transferred to other so-called “midlevel” providers.

The term “midlevel” (not always a popular term, by the way) refers to someone whose training lies “mid-way” between that of a physician and another provider (like a nurse, psychologist, social worker, etc) but who is still licensed to diagnose and treat patients. Midlevel providers usually work under the supervision (although often not direct) of a physician. In psychiatry, there are a number of such midlevel professionals, with designations like PMHNP, PMHCNS, RNP, and APRN, who have become increasingly involved in “med management” roles. This is partly because they tend to demand lower salaries and are reimbursed at a lower rate than medical professionals. However, many physicians—and not just in psychiatry, by the way—have grown increasingly defensive (and, at times, downright angry, if some physician-only online communities are any indication) about this encroachment of “lesser-trained” practitioners onto their turf.

In my own experience, I’ve worked side-by-side with a few RNPs. They performed their jobs quite competently. However, their competence speaks less to the depth of their knowledge (which was impressive, incidentally) and more to the changing nature of psychiatry. Indeed, psychiatry seems to have evolved to such a degree that the typical psychiatrist’s job—or “turf,” if you will—can be readily handled by someone with less (in some cases far less) training. When you consider that most psychiatric visits comprise a quick interview and the prescription of a drug, it’s no surprise that someone with even just a rudimentary understanding of psychopharmacology and a friendly demeanor can do well 99% of the time.

In my own experience, I’ve worked side-by-side with a few RNPs. They performed their jobs quite competently. However, their competence speaks less to the depth of their knowledge (which was impressive, incidentally) and more to the changing nature of psychiatry. Indeed, psychiatry seems to have evolved to such a degree that the typical psychiatrist’s job—or “turf,” if you will—can be readily handled by someone with less (in some cases far less) training. When you consider that most psychiatric visits comprise a quick interview and the prescription of a drug, it’s no surprise that someone with even just a rudimentary understanding of psychopharmacology and a friendly demeanor can do well 99% of the time.

This trend could spell (or hasten) the death of psychiatry. More importantly, however, it could present an opportunity for psychiatry’s leaders to redefine and reinvigorate our field.

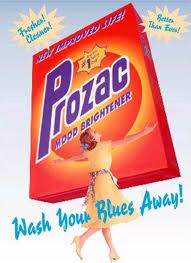

It’s easy to see how this trend could bring psychiatry to its knees. Third-party payers obviously want to keep costs low, and with the passage of the ACA the role of the third-party payer—and “treatment guidelines” that can be followed more or less blindly—will be even stronger. Patients, moreover, increasingly see psychiatry as a medication-oriented specialty, thanks to direct-to-consumer advertising and our medication-obsessed culture. Taken together, this means that psychiatrists might be passed over in favor of cheaper workers whose main task will be to follow guidelines or protocols. If so, most patients (unfortunately) wouldn’t even know the difference.

On the other hand, this trend could also present an opportunity for a revolution in psychiatry. The predictions in the previous paragraph are based on two assumptions: first, that psychiatric care requires medication, and second, that patients see the prescription of a drug as equivalent to a cure. Psychiatry’s current leadership and the pharmaceutical industry have successfully convinced us that these statements are true. But they need not be. Instead, they merely represent one treatment paradigm—a paradigm that, for ever-increasing numbers of people, leaves much to be desired.

On the other hand, this trend could also present an opportunity for a revolution in psychiatry. The predictions in the previous paragraph are based on two assumptions: first, that psychiatric care requires medication, and second, that patients see the prescription of a drug as equivalent to a cure. Psychiatry’s current leadership and the pharmaceutical industry have successfully convinced us that these statements are true. But they need not be. Instead, they merely represent one treatment paradigm—a paradigm that, for ever-increasing numbers of people, leaves much to be desired.

Preservation of psychiatry requires that psychiatrists find ways to differentiate themselves from midlevel providers in a meaningful fashion. Psychiatrists frequently claim that they are already different from other mental health practitioners, because they have gone to medical school and, therefore, are “real doctors.” But this is a specious (and arrogant) argument. It doesn’t take a “real doctor” to do a psychiatric interview, to compare a patient’s complaints to what’s written in the DSM (or what’s in one’s own memory banks) and to prescribe medication according to a guideline or flowchart. Yet that’s what most psychiatric care is. Sure, there are those cases in which successful treatment requires tapping the physician’s knowledge of pathophysiology, internal medicine, or even infectious disease, but these are rare—not to mention the fact that most treatment settings don’t even allow the psychiatrist to investigate these dimensions.

Thus, the sad reality is that today’s psychiatrists practice a type of medical “science” that others can grasp without four years of medical school and four years of psychiatric residency training. So how, then, can psychiatrists provide something different—particularly when appointment lengths continue to dwindle and costs continue to rise? To me, one answer is to revamp specialty training. I received my training in two institutions with very different cultures and patient populations. But both shared a common emphasis on teaching medication management. Did I need four years to learn how to prescribe drugs? No. In reality, practical psychopharmacology can be learned in a one-year (maybe even six-month) course—not to mention the fact that the most valuable knowledge comes from years of experience, something that only real life (and not a training program) can provide.

Beyond psychopharmacology, psychiatry training programs need to beef up psychotherapy training, something that experts have encouraged for years. But it goes further than that: psychiatry trainees need hands-on experience in the recovery model, community resources and their delivery, addictive illness and recovery concepts, behavioral therapies, case management, and, yes, how to truly integrate medical care into psychiatry. Furthermore, it wouldn’t hurt to give psychiatrists lessons in communication and critical thinking skills, cognitive psychology principles, cultural sensitivity, economics, business management, alternative medicine (much of which is “alternative” only because the mainstream says so), and, my own pet peeve, greater exposure to the wide, natural variability among human beings in their intellectual, emotional, behavioral, perceptual, and physical characteristics and aptitudes—so we stop labeling everyone who walks in the door as “abnormal.”

Beyond psychopharmacology, psychiatry training programs need to beef up psychotherapy training, something that experts have encouraged for years. But it goes further than that: psychiatry trainees need hands-on experience in the recovery model, community resources and their delivery, addictive illness and recovery concepts, behavioral therapies, case management, and, yes, how to truly integrate medical care into psychiatry. Furthermore, it wouldn’t hurt to give psychiatrists lessons in communication and critical thinking skills, cognitive psychology principles, cultural sensitivity, economics, business management, alternative medicine (much of which is “alternative” only because the mainstream says so), and, my own pet peeve, greater exposure to the wide, natural variability among human beings in their intellectual, emotional, behavioral, perceptual, and physical characteristics and aptitudes—so we stop labeling everyone who walks in the door as “abnormal.”

One might argue, that sounds great but psychiatrists don’t get paid for those things. True, we don’t. At least not yet. Nevertheless, a comprehensive approach to human wellness, taken by someone who has invested many years learning how to integrate these perspectives, is, in the long run, far more efficient than the current paradigm of discontinuous care, in which one person manages meds, another person provides therapy, another person serves as a case manager—roles which can change abruptly due to systemic constraints and turnover.

If we psychiatrists want to defend our “turf,” we can start by reclaiming some of the turf we’ve given away to others. But more importantly, we must also identify new turf and make it our own—not to provide duplicate, wasteful care, but instead to create a new treatment paradigm in which the focus is on the patient and the context in which he or she presents, and treatment involves only what is necessary (and which is likely to work for that particular individual). Only a professional with a well-rounded background can bring this paradigm to light, and psychiatrists—those who have invested the time, effort, expense, and hard work to devote their lives to the understanding and treatment of mental illness—are uniquely positioned to bring this perspective to the table and make it happen.

1.Sounds like you’re wanting to send psychiatrists to Social Work school.

2. It would also be nice if psychiatrists could take more responsibility in medical management for psych patients who tend to get lousy care from medical providers.

Mindy,

I don’t know about “Social Work school,” per se, but there’s little doubt in my mind that psychiatrists would benefit from learning how access (or, more critically, the lack thereof) to community resources, social services, and various entitlements influences their patients’ well-being.

To put it another way, depression may not be “Depression” if it results solely from extreme financial hardship, and anxiety may not be “Anxiety” if it’s the consequence of an abusive relationship or a traumatic environment. The social and interpersonal context in which “psychiatric” complaints arise are vitally important, and are, unfortunately, largely ignored in mainstream psychiatry.

Dr. Steve, you make an excellent point here. In our society where people are encouraged to seek medical attention for emotional health issues, and some are required to seek medical attention in order to receive needed benefis, it is important for doctors to be able to see not just their whole patient but their patient in social/economic/political context. This is what social workers are in theory trained to do.

Because psychiatrists see people from all sorts of contexts, it is important for psychiatrists to not just rule out more somatic origins of distress (non-psychiatric medical conditions) but also environmental ones and be able to take helpful action. Whether or not psychiatrists should or need to have the breadth of understanding about such issues is up for debate, I do believe that they should at least be able to recognize such issues and how they differ from what they consider their own “turf” (experts on mental disorders), and be able to refer effectively or bring in other professionals to support alleviating distress caused by those environmental factors.

I think psychiatrists should use midlevels like House uses his staff of doctors. I don’t mean abuse and manipulate them. I mean use them as a team to toss around ideas. Two heads are better than one. That would actually be kinda cool. Have a psychiatrist, an NP, a naturopath, psychotherapist, etc, all on the same team tossing around ideas in a room. They all see the same patient and each other in the same building. Throw in an internist or family doc too. I like how House has people from all kinds of specialties on his team. Cameron was an ER doc, Chase and Taub were surgeons, Forman was a neurologist, House specialized in infectious diseases. Psychiatrists can do something similar with midlevels and maybe even other docs.

With advent of the internet, expertise of all kinds has become less important. What this means of course is that administrators and manipulators win as the service itself seems to become more of a commodity. As pointed out in Steve’s post, psychiatric service, properly construed, is not a commodity.

I can’t believe this but I actually ran into a case of something that has concerned me for a long time: I slightly know a rather sociable young man who applied to medical school. He has close to a 4.0 average and three years of hard core research. He is smart, experienced and friendly. He did not get into medical school—- no volunteer service. At least that is his story.

I probably want this smart, adventurous fellow to be my doctor ten years from now. I think he will know his business, he seems to know basic neurology. And the other students, who did their service, if that is something you have to do to get into medical school, people will do that, what does it mean?

Hawkeye,

Allow me to gaze into my crystal ball here. In my opinion, your comment is startlingly prescient, and perhaps worth a separate blog post on its own.

Let me tell you a little secret: it’s not too much of an exaggeration to say that anyone can become a psychiatrist using Wikipedia. Not a great psychiatrist, necessarily, but a “commoditized” one, for sure. I feel well equipped to make this statement because (a) I was trained in the days before Wikipedia, so I know what it’s like to learn without today’s Internet tools, (b) I admittedly rely on Wikipedia as a quick (and surprisingly detailed and accurate) reference source, and (c) I’ve worked in a few of those settings in which I was absolutely a commodity (i.e., no one cared about the quality of work I provided, but simply that I provided it, and filled out the appropriate forms and EMR checkboxes).

I fear that the expansion of HMO-style insurance and Medicaid programs under Obamacare will further narrow the scope of psychiatric practice into those who work most efficiently in the assembly-line mode characteristic of much of modern psychiatry. Furthermore, when no one cares about quality of care (and trust me, the emphasis on “outcome measures” in large health-care systems has little to do with the quality of care a patient receives), the lowest-cost providers will be sought. As a result, midlevels will provide meds, and other mental health practitioners will provide therapy.

I’m not saying that midlevels’ training is on par with Wikipedia, but when a Wikipedia-level of knowledge passes as good psychiatry and psychiatrists don’t respond by bringing something else to the table, the future of psychiatry looks pretty bleak.

“Let me tell you a little secret: it’s not too much of an exaggeration to say that anyone can become a psychiatrist using Wikipedia.”

Steve,

First thanks for your clear headed overview of the future. There is no disease in which a victim cannot become somewhat expert—the equvilant of being able to shoot in the low 80’s on a professional golf course.

My major concern is that psychaitrists have neither the time nor the incentive to deal with long term side effects. Example, the metabolic problems caused by atypicals can be much greater than the disease they are meant to treat. I am not sure that all pschiatrists who prescribe these order regular glucose checks. A patient can self check, say once a week.

These are not “mid-level” matters, and only a well trained doctor is able to handle them.

Very interesting, let me share with you a real story about “sleeping tablets” and “cares” http://dotdos.net/2012/07/01/orfidal-si-precisa/

¿Why not psychiatrists can do that?

(I apologise for the translation into English)

Actually I was speaking to a contact at Alexander David several days ago. I’m sure he mentioned them in passing but for the life of me I ca87#n21&;t recall what he was saying as we were discussing Ntog. I’ll get back to you on it.Dan

Psychiatrists should be generalists, and should consider all influences on mental health from the cellular to the sociological. Obviously, there will be specialists in some of these areas (cell biologists, sociologists, specialized psychotherapists), but we should have the overview. This is the path to avoiding “psychiatry as commodity” and the only solution I see to avoid being boxed into mere drug dispensing (not that this isn’t a valuable service). See:

Good point. I’m reminded of how medical students complain that organic chemistry is a prerequisite for med school. Do doctors use organic chemistry on a daily basis? Not at all. However, studying it for a year gave me a deep appreciation for the complexity of the molecules underlying life, valuable lessons in how to assimilate a large body of information and make sense of it all, and enough knowledge to know when a problem is likely to have a physical, chemical, or biological basis. Devoting an equivalent amount of time during residency to the teaching of psychotherapy principles, cultural influences on mental health– or even social work– would likely be met with the same disgruntlement, but (IMHO) would make for a generation of better psychiatrists.

[…] Click Here to Read: Turf Wars by Steve Balt on the Carlat Psychiatry Blog: Thought Broadcast. Explore posts in the same categories: General News […]

While your ideas sound good, there are some contradictions. If MD’s don’t want to perform services they aren’t reimbursed “enough” for, then fine. If “mid-level” people now provide these services, (at lower fees) then fine.

This sounds like a retro-conversation of the 1990’s when psychiatry performed many services, including psychotherapy, which it ceded in order to make more money with meds-management. MD’s once claimed “superiority”, esp. thru its medico-legal knowledge, then gave up other skills (psychotherapy, community skills, etc.) to maintain the higher financial reimbursement of medication management.

It will be difficult to come back and re-assert “superiority” over other professions who have since excelled at these other skills.

I also notice you make no mention of clinical psychologists who have Ph.D.’s, 5+ years of graduate education, research publications (dissertations) and solid psychotherapy training. By focusing on RNP, MSW, etc. you are diminishing the full field.

Dr McCarthy,

Indeed you are right that practitioners are free to choose whatever practice environment they wish, whether for reasons of personal satisfaction or personal remuneration. I offer my commentary from the perspective of someone who never personally ceded any responsibility to others; in fact, as a relatively recent trainee I was shocked at the relative absence of anything other than psychopharmacology in my training, and see virtually nothing being done by others more powerful and connected than I, to reverse this trend.

My failure to mention PhD-trained psychologists was deliberate. Of all the mental health practitioners who pose the greatest threat to the psychiatric profession, it is those doctoral-level psychologists who, as you say, have in most cases shown mastery of psychotherapy skills, have not been tainted by the false promises of psychopharmacology, and who, interestingly enough, are probably better equipped to critique behavioral sciences research (including clinical trials of new drugs) than most physicians.

If “midlevels” continue to gain prescribing authority, the result may be a continuation of our field’s status quo, albeit with less involvement by psychiatrists. If psychologists obtain prescribing authority, there may be no need for psychiatrists (or midlevels?) at all.

Im-Patient, here (Actually, it’s Annalaw… I’ve commented a few times on subjects that lay folks can ‘competently’ discuss. My own psychiatric ‘journey,’ as an illustration, first: Saw a psychiatrist with awesome credentials, best residency, etc., and she was clearly skilled and I eventually began to trust her and think the ‘meds journey’ would work out. Then she left. Next up, a newbie, barely out of school, who sat at a computer and just handed me scripts after about 10 minutes. Next, a ‘locum,’ or temp, there for only a few months – at least she told me that up front – good thing, because I liked her and wouldn’t have minded staying with her. Next, uh… No One. I held out for what I wanted (a permanent psych, preferably female, with at least a few years’ experience.) Got a call the other day from the clinic saying they wanted to book my first appointment with her. I gladly did so, only to find out it would be for 15 minutes!!! Thanks to reading this site and others like it, I objected, saying how will she know what to do in only 15 minutes? The clerk grudgingly said that’s what they were instructed to do, but she’d book it for 1/2 an hour. My decision – to go, but tell her first off, NO med changes of Any Kind until I’ve spent at least an hour with her. Whether that’s in the form of 1 appointment or 4.

I have seen NPs et al come into the ‘med management’ role, and am not opposed, so long as there is active supervision and the ability to access the psychiatrist without feeling like a ‘trouble-maker.’ Yet I agree w/ Dr. Steve, when he says that psychiatrists can start “reclaiming some of the turf we’ve given away to others. But more importantly, we must also identify new turf and make it our own—not to provide duplicate, wasteful care, but instead to create a new treatment paradigm in which the focus is on the patient and the context in which he or she presents, and treatment involves only what is necessary (and which is likely to work for that particular individual). Only a professional with a well-rounded background can bring this paradigm to light, and psychiatrists—those who have invested the time, effort, expense, and hard work to devote their lives to the understanding and treatment of mental illness—are uniquely positioned to bring this perspective to the table and make it happen.”

Is that to say nurses and others do not have roles here? Of course not. However, I don’t care if the Doc I have an appointment w/ IS a psychiatrist – 15 minutes ain’t gonna give her enough information to alter my current med regiment and start me on something new. If the cost-conscious facilities use nurses or other ‘mid-level’ providers to obtain this valuable info, it’s a lot better than not having the info at all, although better still would be the docs going a bit ‘old school’ and re-learning how to communicate sans the computer, with their patients who are vulnerable, just by being there!

For a while, I followed a blogger / poster I really liked who talked about the need for understanding the most vulnerable folks, those who have attempted or who are thinking of suicide (no, I’m not…). She is right in saying that there’s such a need for safe places where such folks can be understood and cared for while they work through their issues in a non-coercive manner – that doesn’t exist today, as far as I know. Part of what psychiatry could do, perhaps, when redesigning their profession, is give considerable thought to how to help folks in non-coercive ways, via meds, therapy or what have you.

what made my first and 3rd psychistrists ‘special’ was that they Talked To Me – I already have a social worker therapist, so they were not trying to supplant her. They were simply trying to find out enough about me so that they had a basis to formulate the proper plan. I didn’t let the 3rd one switch me, as I knew she was only there for a few months, choosing instead to wait until I got someone ‘permanent.’ Psychiatrists – writing in here and airing views is wonderful. Go to your professional meetings and do the same (yeah, I know, easier said than done.). Patients: I was terrified when I first went to the psychiatrist – now, I’m ready to go into my 4th doc and let HER know what I want and how I want things to go. I will be appropriate and reasonable. But if it’s not a connection, I’m moving on. Long, rambling post – in ‘short,’ the entire profession needs a top to bottom overhaul. Just my 2 cents, from a patient.

The accident of finding this post has brntigehed my day

Domnule Ciocan, CE sa dialoghezi cu Antonescu??? Cu Voiculescu???? Cu Ponta???Serios… Pare frumos, inaltator, de bun simt cveea ce spuneti, dar nu se poate nimeni baza pe spusele vreunuia dintre astia. Si ce sa dialogheze TB cu ei? Un dialog, presupune si negociere, adica CE sa negocieze cu ei? Ca stim ce vor EI sa negocieze…

Steve,

A few comments:

I agree with your statement, “Patients, moreover, increasingly see psychiatry as a medication-oriented specialty, thanks to direct-to-consumer advertising and our medication-obsessed culture.” But you let psychiatry off the hook here. A few decades ago, psychiatry actively sought this sorry situation as a way to claim its own market niche – in response to losing psychotherapy market share to psychologists, social workers and counselors. Since then, mainstream psychiatry has done everything it can to maximize PhARMA’s mythology of “medication.” This was not just a few leaders – the vast majority of psychiatrists at least went along, and often actively abetted the effort.

You write, “It doesn’t take a “real doctor” to do a psychiatric interview, to compare a patient’s complaints to what’s written in the DSM (or what’s in one’s own memory banks) and to prescribe medication according to a guideline or flowchart. Yet that’s what most psychiatric care is.” True, but that doesn’t mean “mid-level” professionals should perform this function. NOBODY should perform this function – it’s lousy care, no matter who does it. The 15 minute med check is demeaning to patients, who deserve someone to take the time to really know them. And do we really think mid-levels will be any more restrained in prescribing than psychiatrists? And do we really think mid-levels will make these dangerous and largely ineffective drugs any less so? The first thing psychiatry must do is simply disavow psych drugs as first-line treatment (and that’s still being extremely generous to drugs) – and take a strong stand against 15 minute appointments.

You correctly criticize the “current paradigm of discontinuous care.” And I agree with your desire to expand psychiatric training to a broad range of psychosocial issues. But the only way one profession could handle all the roles you want psychiatrists to take on would be to trivialize most of those roles – kind of like Daniel Carlat’s use of 20 minute therapy sessions, probably done monthly. I suggest variations of the Open Dialogue model, in which various professions form a treatment team for each first episode psychosis client, and stay with the client for years, if necessary.

This may not be as cost-ineffective and staff-turnover-vulnerable as it seems. There would be more money to pay for staff and longer appointments if less were paid to drug companies for their drugs, and to hospitals for hospitalization (Open Dialogue rarely hospitalizes). Since the treatment would also be more effective, patients would not so often become chronic. And if “mental health” care came to resemble less of a production line, it might be possible to retain staff longer.

Finally, I strongly disagree with your statement, “Only a professional with a well-rounded background can bring this paradigm to light, and psychiatrists—those who have invested the time, effort, expense, and hard work to devote their lives to the understanding and treatment of mental illness—are uniquely positioned to bring this perspective to the table and make it happen.” With a few exceptions like yourself, psychiatrists are the least well-rounded, most blindly locked into a narrow medical model, of any major players in “mental health.” Your list of what you want to see in psychiatry training is striking for its current absence, and is much more in synch with the training and theoretical frameworks of psychology and social work.

I also think psychiatry’s expertise in psychopharmacology and pathophysiology are not “expertise” at all. Both subject areas are so shot through with pseudoscience, fraud and interpretation blinded by medical model bias, that knowledge of them is often worse than no knowledge at all. This may seem extreme, but a profession that still does 15 minute med checks, blows smoke about chemical imbalances, and (as you have noted) defends antidepressants against Kirsch instead of saying, “ok, let’s find something better then” – such a profession is not, as a profession, operating from knowledge or integrity.

Psychiatry could have a role. It could, as you advocate, take a broad psychosocial view of humans – that would be welcome. Psychiatry could also use its “scientific” credibility to crusade against the myths and use (usually, inaccurately called “overuse”) of drugs (also misnamed “medications”). The drug mythology constructed by PhARMA and psychiatry is so pervasive that this would take a generation – and, who knows – maybe by that time real scientists may have produced drugs that actually work for limited times in extreme cases? ¬

Peter Dwyer says: “these dangerous and largely ineffective drugs”

This is the point. Some of these drugs work, brilliantly, for some people with little side effect. I suspect this is relatively rare.

More to the point, and by example: what is your metabolic system like after three years on an atypical that has kept you afloat, but with so many side effects that you might not be able to hold a job?

And more, more to the point, would you have done well on a generic mood stabilizer?

Hawkeye – You’re still operating on assumptions that need to be questioned. You don’t have to accept Anatomy of an Epidemic, The Emperor’s New Drugs or the Myth of the Chemical Cure as gospel to see that they raise critical questions about assumptions you and virtually the entire “mental health” system aren’t questioning, but should:

Open Dialogue should make you ask, not “would you have done well on a generic mood stabilizer,” but “would you have done as well or BETTER – short and long term – in a generally drug-less Open Dialogue program?” When Open Dialogue reports 80% of first episode psychosis patients having essentially full recovery at 5 year follow up, why NOT ask that question? There’s nothing (at least nothing honest) like those results in conventional psychiatry.

Another assumption that needs to be questioned: thoughtful psychiatrists like Steve often justify their field by saying that every so often the pills work really well. We need to ask: but how many lives were wrecked, severely limited, or just didn’t do as well as they might have in Open Dialogue, just to get to that one who responded so well to the neuroleptic? And how will that one person be doing in 15 years, mentally and in general health? And, if one tenth the resources of pill research were devoted to the psychosocial, would there be a non-drug method that helped that one person just as much?

Peter,

Points well made. I guess when I say psychiatric drug, in my mind I really mean lithium–a sometimes very effective treatment whose dangers are well understood and easy to deal with.

A beloved friend of mine died young, I belive of neuroleptic poisioning. I am with you.

Just so you know… we patients are more or less ‘forced’ to see psychiatry as a medication-oriented specialty, because that’s what it has become all about.I was very hesitant to try meds, at first, and it was only through slow acceptance of them and a good psychiatrist who took her time was I able to deal with them and arrive at an acceptable result. However, when I am told by the clinic’s clerk that they are ‘required’ to schedule 15 minute appointments (for new patients!), you have to know that’s the administration talking – with its eye on the bottom line. Certainly not this patient’s preference. While it is true, there will always be folks who just want to ‘take a pill and feel better,’ as patients, we really have no choice but to go along with how ‘psychiatry’ is presenting itself these days – as medication providers.

As I mentioned above in my post, I don’t think a psychiatrist (or anyone else for that matter) will know enough about me in 15 minutes to prescribe a long-term regimen of drugs, particularly when prescribing 2 or more meds, as sometimes occurs. No one solution is right for every patient – it takes time to ascertain who the patient is, how they react to meds and also to life. It takes time to know what the ‘right’ med and the ‘right’ dosage is for each person. Rocket science? Perhaps not. True, someone with less training than psychiatrists have might be able to match symptoms to a medication, but at least on the receiving end, psychiatry involves intuition, experience, and a methodical exploration into the person’s background and issues.

Just doing a little reread.

“If we psychiatrists want to defend our ‘turf,’ we can start by reclaiming some of the turf we’ve given away to others.”

Well, this isn’t a surprising line in a blog entitled “Turf Wars.” I just question a lot of the judgement and falsehoods in this statement in context. Psychiatrists didn’t give other mental health professionals “turf.” Psychiatrists were the first on the scene, monopolized it, and then alternative views from different perspectives arose to challenge psychiatrists’ domination of mental health care and what mental health and mental health care means. This coincided with various social movements in general. Psychiatrists were forced to compete for “turf,” and were losing. So instead, Psychiatry primarily retreated into biomedical paradigms where they could still have an edge (medication) and keep societal respect (as physicians). Saying psychiatrists gave away turf makes it seem like psychiatrists always had the power to do so, and that is just not the case. Other perspectives challenged Psychiatry and those perspectives gained ground (for all sorts of reasons). And what makes Psychiatry think it can “reclaim” lost turf? From who? With what authority? Bullying its way into publishing a disaster of a new DSM certainly won’t help.

“But more importantly, we must also identify new turf and make it our own—not to provide duplicate, wasteful care, but instead to create a new treatment paradigm in which the focus is on the patient and the context in which he or she presents, and treatment involves only what is necessary (and which is likely to work for that particular individual).”

This somewhat contradicts what you said above. Reclaiming turf is in many ways providing “duplicate” care. But really, reclaiming means that psychiatrists will only do that care and leave other mental health professionals with new turf to find. As for the new treatment paradigm you seek, other mental health professionals already have the paradigm you describe, particularly social workers. Sending psychiatrists to social work school is not a bad idea if you want that turf. Social workers and other mental health professionals cannot always live that paradigm because they work in a system led by psychiatrists in biomedical frameworks.

Instead of trying to reclaim and make war, how about work together with other professionals? If psychiatrists share the same paradigm of care (the one you suggest) with other mental health professionals, there is no reason they all can’t work together in a more egalitarian way. Psychiatrists keep their ability to prescribe, but that shouldn’t be seen as “turf” in this context, but simply expertise, potentially valuable but no more valuable than other kinds of expertise other professionals bring.

If you turn this into a fight, a turf war, as the APA has certainly done, I believe Psychiatry will be on the losing end.

I should clarify that I believe psychiatrists were the first modern mental health professionals on the scene. They came into prominence with their own social rationalist social movements and had to fight for “turf” with religious leaders and institutions.

Nathan, I agree. Myself holding licenses in both social work (MSW) and psychology (PhD) my professional life started in the 1970’s, and I lived through these earlier turf wars. We in these (and other) professions resented and fought back against what psychiatry saw as their “turf”, especially when we soon had strong expertise in psychotherapy and community work. Personally I found this especially hard when I worked for a few years in a psychiatric hospital (esp. outpatient areas) and the new psych residents knew much more about medicine but myself and my colleagues know much more about family work, systems work, complex and longer term psychotherapy, and parts of diagnostic interviewing that included detailed psychosocial material. Yet we were to defer to younger, less experiences, and less trained (in all of these area) residents and psychiatrists. In the best of cases, we worked as a team for the patient with mutual respect for each other’s expertise. In the worse cases, the MD dominated the “turf” with with minimal expertise.

Although anecdotal, I recently had a complex psychotherapy case where the pt. needed meds. The young psychiatrist wanted to take over the whole case because he told me he also “studied psychotherapy” in his training, which turned out to be one seminar and one or two cases. Yet I have 30+ years experience, years of advanced post-doctoral study in individual therapy, group, family and organizational therapy, many publications, etc. I was appalled that this MD actually thought, in the patient’s best interests that he was as qualified (if not more so) than I because he also saw psychotherapy as his “turf”, since he was an MD. (PS: the pt. did see him for a month and then quit).

It is these less trained and experienced MD’s who believe it is also their turf because they (1) took one seminar and a few short-term cases and (2) have MD’s. Don’t they know that even the MFT’s, MSW’s, MHC, etc. have two years full time study and 3000 hrs. of experience in psychotherapy in order to be licensed?

So, from that point alone, I think it is impossible for MD’s to “reclaim” (on what grounds?) their “turf” unless they are willing to take years of study and practice in psychotherapy. In the “old days” MD’s did have much more expertise in therapy, since (for good or bad) they often also trained for 4 years in psychoanalysis, in addition to prescribing (much more limited at the time) use of (fewer) mediations.

Of course there are exceptional MD’s who have also sought out advanced training in psychotherapy (and beyond simplistic CBT techniques), but they are now rather rare.

PS: I am enjoying this conversation.

Dolores,

Thanks for your observations. As an early career psychiatrist, I obviously wasn’t around for the earlier “turf wars.” In fact, I entered training in the late 1990s and early 2000s when the boundaries were well established: psychiatrists gave drugs and therapists talked to people, and since both tools were equally powerful, there was enough room for us to coexist. However, it didn’t take a rocket scientist (although apparently it required someone with more training than a psychiatrist– or, in my case, personal experience with mental illness) to figure out that drugs weren’t the panacea we had hoped, and in fact often caused problems of their own. But since no one in the psychiatric hierarchy seemed to care, I’m now starting my solo career behind the proverbial eight-ball: I’ve been educated extensively in psychopharmacology but I look longingly at the greener grass on the other side of the fence, where real change (and what I really want patients to experience) happens. Unfortunately, I get paid more to do what I often find more repugnant.

BTW, as I launch my private practice, I’ve been told by two respected colleagues that if word gets out that I do both medication management and psychotherapy, I won’t get any referrals from therapists because they might think I’ll take their patients! Nothing could be further from the truth: I see my goal as helping to straighten out (or “clean up”) the biology and return them to wherever the most therapeutic interaction will take place– which is most likely with that therapist, and not from a handful of pills from me. And while yes, I sought training and experience in therapy above and beyond what I was taught in school, I do recognize my limitations and encourage the patient to seek whatever and whoever works for them.

I agree with you that a psychiatrist whose area is not psychotherapy,or has only taken a seminar in it, is not the ideal candidate to serve as psychotherapist.

My issue with MFTs is that they don’t necessarily treat mental illness. They could theoretically build a whole practice around couple’s counseling, grief counseling, etc, and rarely to never treat a mentally ill person. It is a given that a psychiatrist will treat a mentally ill person and so they may have more experience in that area.

My anecdotal story is that I saw an MFT and the MFT asked me to DIAGNOSE MYSELF. Quite literally, during the first session, the MFT told me she wouldn’t get reimbursed if she didn’t give me a diagnosis. So she whipped out a DSM, read off some different disorders to me, and asked me which one best fit. She even read me the different kinds of Bipolar Disorders (Cyclothymia, Bipolar 1, 2, NOS), and then asked me if any of those sound like me…

I might actually choose a psychiatrist with less psychotherapy experience, but more experience with mental illness, before choosing a really experienced MFT who doesn’t really treat mental illness all that often and diagnoses Bipolar Disorder by reading a description out of the DSM to the patient and asking if it fits.

Steve: Thank you for both your clear, thoughtful and respectful responses. I appreciate your perspective as a relatively early career psychiatrist. I assure you that, as a psychologist, I have no interest whatsoever in prescribing meds – I think it is outside my areas of expertise, am concerned about meds interactions, and other straight medical concerns. In spite of other psychologist’s position, I think we need extensive training to do so, and I have my hands full with psychotherapy and psych testing.

But I wonder what you see as some of the specific expertise that psychiatry can offer beyond meds and consults, and would you need more training for this?

Mara: I agree that what happened to you with the MFT was inappropriate. If fact, MFT’s are really not trained to do individual therapy. However it is true that insurance companies require a DSM diagnosis, and many non-MD’s are quite casual about it. The reason is, unless you have a severe mental illness they would rather “assign” you a more benign one. They really shouldn’t let you “choose” but I suspect she was trying to “collaborate.” Anyway, you probably shouldn’t see a MFT for an individual problem. If it were a couple’s issue then it’s a sort of crazy insurance company issue.

Oh wow. Thanks Dolores. I didn’t even know that about MFTs not being trained for individual therapy. I was referred by my insurance company. Maybe it’s different where you live? I’m from California, and many MFTs provide individual therapy here. No joke. There are far more MFTs in my area than psychologists or LCSWs, and the MFTs provide individual therapy.

Mara: I just checked, and there are differences by state and Calif does license MFT to do therapy.Many states do not. However, I checked the course requirements for MFT training and they are the most minimal in individual therapy and “mental health/psychiatric.” The bulk of the courses are in marriage counseling, sex therapy, family/children issues, etc.

Still I would not generally go to a MFT for individual therapy, even if the insurance refers you. Remember, the insurance prefers the cheapest, lower level therapists because they can pay them less.

Nathan,

I should point out that I don’t see this as a “fight” or a “war” at all, although judging by the vitriol leveled by some of my peers towards “midlevels” and others in the mental health profession, there is indeed a competition taking place. Like you say, unless we can offer something other than just name-calling, we psychiatrists will be on the losing end. Unfortunately, the leaders of the APA don’t seem to see things this way, and when I offered my observations to the president of my state psychiatric society last spring, they were met with a shrug and, “yeah, that’s the way it is.”

Incidentally, if psychologists can take courses to become prescribers of psychiatric medication, then psychiatrists should be able to take courses in social work. I don’t see many psychiatrists clamoring to do the latter, although many psychologists lobby for their right to drug people. I’ll let you decide what the ultimate outcome to society (and to our respective professions) will be.

I strongly agree that the field of psychiatry is in great need of an overhaul/remodel. As a consumer, I can express my frustration with the current model with the following anecdotal account: I received outpatient treatment from a revered and knowledgeable psychiatrist following my discharge from a psych hospital. This insightful professional basically “worked” himself right out of a job. He had a holistic approach even though his compensation for services was derived almost exclusively from medication management. In my particular case, he weaned me off, of the SEVEN psychotropic medications I was prescribed when hospitalized, over a fourteen month period and at the “end” scheduled my twenty minute visits with him three months apart. By titrating me off these meds , he effectively lost my business because the powers that be at the insurance companies decided….even after I appealed….that he should not be compensated for treating me if he was not going to prescribe me medications. What a shame! As a result, I lost the ability to schedule appointments with him. Ironically, this same insurance company sent out forms to be completed by a licensed physician to update my “disability” status and refused to accept the submission of these forms by my treating PHD psychologist because he is NOT a psychiatrist licensed as an MD. The guidance and help I received from this psychiatrist was instrumental in my recovery process and allowing me to live independently in the community at large and sadly I am unable to continue this positive supportive relationship without the insurance company paying for it.

Reform is sorely needed,albeit complicated.

As I’ve said many times, I don’t see why nurses or PAs or just about anybody can’t do as good or bad a job providing psychiatric care as psychiatrists and other MDs.

If psychiatrists could argue their use of psychiatric drugs was safer and more effective than other doctors, and doctors could say their use use of psychiatric drugs was safer and more effective than non-doctors, this might not be true.

But it is true. Psychiatric care at anyone’s hands is a roll of the dice. If your doctor or psychiatrist is clueless about adverse effects, as most of them are, and you run into problems with the drugs, you’re up the creek. And don’t get me started on unwarranted prescribing.

On the other hand, nurses might be wising up, see

Nurs Ethics July 2012 vol. 19 no. 4 451-463 Dundee et al First, do no harm: Confronting the myths of psychiatric drugs:

“The enduring psychiatric myth is that particular personal, interpersonal and social problems in living are manifestations of ‘mental illness’ or ‘mental disease’, which can only be addressed by ‘treatment’ with psychiatric drugs. Psychiatric drugs are used only to control ‘patient’ behaviour and do not ‘treat’ any specific pathology in the sense understood by physical medicine. Evidence that people, diagnosed with ‘serious’ forms of ‘mental illness’ can ‘recover’, without psychiatric drugs, has been marginalized by drug-focused research, much of this funded by the pharmaceutical industry. The pervasive myth of psychiatric drugs dominates much of contemporary ‘mental health’ policy and practice and raises discrete ethical issues for nurses who claim to be focused on promoting or enabling the ‘mental health’ of the people in their care.”

Can I be one of the “experts” saying psychotherapy should be taught to residents?

http://www.clinicalpsychiatrynews.com/index.php?id=2407&cHash=071010&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=59135

Dinah’s article says: “There is a vocal (and growing) body of patients and ex-patients who feel they have been harmed by psychiatric treatments. It may be that patients who meet with psychiatrists for brief, time-pressured encounters are more likely to feel victimized by psychiatric treatments. The media feeds this anti-psychiatry frenzy when it portrays psychiatrists as being all about medications. Psychiatrists are no longer seen as being interested and caring, and this is not good for our profession.”

Well, I’m glad somebody noticed. Oh, by the way, ACTUAL injuries are occurring, it’s not the patients’ imaginations.

I am for this, if we define “psychotherapy.” For various reasons, many people define “psychotherapy” as “cognitive-behavioral therapy” (sometimes DBT too), which is perhaps the most limited and simplistic form of therapy.

I have seen many articles written for psychiatrists that equate “talking with the pt” as “psychotherapy”. Some CBT skills that sound impressive (“cognitive restructuring”, for example) are hi-tech ways of saying “think about it differently.” I have read article on say, smoking cessation that recommend “cogntiive-behavioral therapy”, which sounds more like common sense and encouragement than “therapy.”

IMO psychotherapy (in a real sense) is a complex endeavor and if MD’s now do “it”, I hope the training is (at least) as rigorous as most other professions that have 60 credit MA programs, at least half of which is devoted to specific psychotherapy training and then apx. 1500-3000 hours of direct psychotherapy and supervision.. If that is what MDs learn, great. But having “a few” therapy cases, one or two seminars and some supervision in not sufficient.

Dinah,

Thank you for the link to your article. As a psychiatrist who has only recently completed residency training, I must say that the description of your supervisory interactions with residents is entirely accurate. Many residents are indeed “too busy” to engage in serious psychotherapy training. And as Dolores correctly points out, “psychotherapy is a complex endeavor” and many hundreds of hours are required to ensure proficiency. But when psychiatric residents are also being tempted with $200K+ offers for “med management” jobs, it’s not surprising that residents show little interest in learning anything other than psychopharmacology.

To me, the real advantage of learning psychotherapy is not necessarily to learn how to provide therapy according to a rigorous, evidence-based and manualized protocol (although there are advantages to that, too), but to capitalize upon something you mention in your second bullet point: namely, “to learn the importance of active listening and understanding unspoken components of interactions.” Psychiatric patients are patients second, but people first. I have always been astounded by what I can learn from my patients simply by listening, observing, and, for lack of a better term, “being real” with them, and not by looking at them as symptoms, disorders, or diagnoses.

I couldn’t agree more (of course). Even for residents who never again treat a patient with psychotherapy, the active listening skills, appreciation for dynamic unconscious/conflicts, and simply listening to the patient’s story before jumping to diagnose are hugely important benefits. More here:

http://blog.stevenreidbordmd.com/?p=280

http://blog.stevenreidbordmd.com/?p=418

It might already be to late for psychiatry, etc. I practice Psychosomatic Healing and handle nearly everything the Psychiatrist, Psychologist, Psychotherapist, Counselor and 70% of what the MD treats without any labels or medication.

Without workable psychotherapy [Not Psych Psychotherpy], the above practises are destined to treat the symptoms of psychosomatic illness through the acute and chronic stage without any cures in sight.

“The human body was found to be extremely capable of repairing itself when the stored memories of pain were cancelled. Further it was discovered that so long as the stored pain remained, the doctoring of what are called psychosomatic ills, such as arthritis, could not result in anything permanent.”

http://www.psychosomatic-healing.co.nz/dianetics.html

Kevin Owen

Psychosomatic Healing

http://www.psychosomatic-healing.co.nz

Handling Trauma With Advanced Psychotherapy

Handling the stress related to all illness.

With a reduction in Mental and Physical Stress comes an improvement in health.

“Experts estimate that psychosomatic illnesses account for up to 70 percent of mans ills, including being too fat or too thin, migraines, allergies and other afflictions not strictly caused by physical reasons.”

Cases Handled With Psychosomatic Healing Kevin Owen

http://www.psychosomatic-healing.co.nz/cases.handled.html

“It doesn’t take a “real doctor” to do a psychiatric interview, to compare a patient’s complaints to what’s written in the DSM … and to prescribe medication according to a guideline or flowchart. Yet that’s what most psychiatric care is.”

Agree with the first two points, but totally disagree with the latter. I never encountered an NP or similar that had the faintest idea of how to medicate, except with a flow-chart. For example, they totally ignore the differing anti-cholinergic values of different anti-psychotics. In consequence, when patients with any level of cognitive deficit presents with psychotic symptoms they do not see any reason to select a neurotropic with the least anti-cholinergic activity or to avoid atropine in any form. They treat Alzheimer’s patients with cholinesterase inhibitors and then they give them diphenilhydramine, and… I could go on forever. To be a “real doctor” is to know the medications, their chemistry, their similarities and differences, the relationships between them, their beneficial and harmful effects when used alone and in combinations, why and how to avoid polypharmacy and redundant prescribing (more than one anti-psychotic and/or more than one anti-depressant at a time, as an example,) be cognizant of the metabolic pathways and half-life, and etc. That is, employ the medications judiciously, And that you do through knowledge, as well as experience. Worst, this does not only apply to NPs or similar, it applies to psychiatric residents and a large portion of active psychiatrists. The ignorance can be staggering, and dangerous and flow-charts are no remedies for ignorance. In conclusion, God save the patients from the prescribing non-MDs, and some MDs as well. Unfortunately, I have to agree that “that’s what most psychiatric care is.”

“employ the medications judiciously” — very true, from what I’ve seen, it’s the extraordinary psychiatrist who does this. Non-MDs can provide psychiatric drug treatment that equals that of most MDs — in complacency and ignorance.

Amen!

I really apraicepte free, succinct, reliable data like this.

Probabil aceste proiecte au fost pe ordinea de zi si erau in proces de aprobare de pe vremea cand Elena Udrea era ministru la MDRT, dar nu a mai apucat sa le aprobe, iar actualul ministru sau alte persoane se lauda cu aceste proiecte, cu aceste lucrari desi nu le apartin…

[…] Click here to read more. Share this:EmailPrintFacebookStumbleUponTwitterDiggLinkedInRedditPinterestTumblrLike this:LikeBe the first to like this. This entry was posted in MD and tagged MD, Mental Health, psychiatry, psychology, Steve Balt. Bookmark the permalink. ← Cases of Filicide: Do 911 Operators easily recognize medication-induced psychosis? […]

In some ways, your description of the ideal psychiatrist comes very close to the description of a family physician. (I am one.) Our purpose is to take all that we understand through the breadth and depth of our training in biological, social, and psychological spheres, and to figure out with the patient, the most effective remedy to their problem. There is a limited amount of time and resource (the reality of existence) and we must use what is available. Evidence based guidelines and quality measures say almost nothing about real quality because each of these is piece-mealing the care of the patient. It is easy for a lesser qualified person to look good on paper, and there is no guarantee that the more highly qualified person will fare better every time. Expertise is there so that when the opportunity arises for change–sometimes this is rare–the prepared genius can take advantage and make a long-term difference. I don’t really see how this can be measured, at least not through patient satisfaction surveys or quality measured aimed at tracking compliance with protocols. The psychiatrist should be the wise person on the mountain, and as a society, we must assure that such people continue to exist.

Why as a family physician do I seek the guidance of a psychiatrist? I’m personally involved in prescribing many psychiatric medicines to my patients. I personally do community building work with patients in order to prevent suicide (and most of this involves social and policy solutions, it turns out). I send a person to a psychiatrist who is spiraling out of control, or who taxes the reserves of my WISDOM. The psychiatrist has seen many more heavy-duty instances of severe mental disturbance and has the biological, medical, and social experience (I hope) to handle the case. For instance, a father with severe low back pain, opiate addiction, and suicidal ideation whose family can no longer take care of him–the whole family is starting to go to pieces. I trust that the psychiatrist is the best person in town to handle the entirety of the vexing situation. I truly believe that she, as a class, is. The psychiatrist should be the guru with the wisdom on the hill. The guru needs deep and broad life experience working in a specialized context. I’m glad we still have psychiatrists around.

Oops–I didn’t mean “psychiatrist who is spiraling out of control!” Should have read my post before posting it! I think you know what I mean!..a patient who is spiraling out of control.

[…] be more effective, offering lower reimbursements for psychotherapy and complementary services, and inviting practitioners with lesser training and experience (and whose experience is often limited exclusively to offering pills) to become the future face of […]

I’m a different kind of psychiatric nurse practitioner–I studied to be a psychologist in the 80’s, doctoral training as psychotherapist close to dissertation and didn’t finish due to life’s travails and picked up master’s in clinical psych then went on to be family nurse practitioner at Univ Colorado, then psych NP from Vanderbilt Univ all the while working full time or close to it and watching psychiatrists on the psychiatric units, outpatient offices do their thing–I’ve probably watched over 100 psychiatrists in my years working as a psychotherapist, individual/family therapist, emergency psych clinician and I have to tell you most of them really were not good at therapy. There are always the bright lights in any field and I believe this is because of what you talked about in your broadcast–therapy went out of style and meds were the training and it shows.

I do believe Nurse Practitioners are as good as their residency–just like for physicians–then they can go on and get the psychotherapy training that any good psychologist needs–again-

Take home messsage docs–don’t judge a practitioner by their medical school, nurse practitioner school–judge the person by their clinical experiences, diverse backgrounds, etc. because there are nurse practitioners like myself who are experts in their field just like there are docs who are very good at what they do and there are docs who are just not very good!

“psychotherapy training that any good psychologist needs–again-”

You might find that Psych Psychotherapy is now obsolete. I handle nearly everything the Psychiatrist, Psychologist, Counselor, and much of what the Medical Practioner handles, without drugs and diagnosis, with psychotherapy [Not Psych Psychotherapy] making that practice old and clumsy.

Welcome to 20th Century Mental Health.

“The human body was found to be extremely capable of repairing itself when the stored memories of pain were cancelled. Further it was discovered that so long as the stored pain remained, the doctoring of what are called psychosomatic ills, could not result in anything permanent.”

http://www.psychosomatic-healing.co.nz/dianetics.html

Kevin Owen

Psychosomatic Healing

http://www.psychosomatic-healing.co.nz

Handling Trauma With Advanced Psychotherapy

Handling the stress related to all illness.

With a reduction in Mental and Physical Stress comes an improvement in health.

The Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Monopoly Gives Way

In sum, billions training therapists in and treating clients with CBT to little or no effect.

http://www.scottdmiller.com/?q=node%2F160

[…] health/primary care clinic in which professionals like Dr Moore can consult with a psychiatrist (or another “psychiatric prescriber”) to prescribe. This arrangement has been shown to work in many settings. It also allows for […]

Reading your insights on the need for change in the psychiatric landscape, I don’t quite understand why a psychiatrist would not embrace the role of a PMHNP.

Per your posts, current demands and time constraints of the psychiatrist does not allow for the comprehensive evaluation/care of patients as a thorough MD such as yourself would hope for. Implementation of a PMHNP in their practice for follow ups, medication adherence evaluation etc. would allow for more time with initial patient interaction and care planning. Intermittent thorough re-evaluation with the psychiatrist should be mandatory, however, NP’s are also very well suited to evaluate labs and medication effect, look for signs of EPS and emphasize ongoing dietary concerns and non Pharm strategies for better physical and mental health.

I believe we all have a significant role to play for improved delivery of care in mental health. If you were to ask most PMHNP’s of their intent; it is not to take on the role of the MD but to be a member of a team of professionals wishing to provide the best care for the patient.

Somewhere along the changing model of health care delivery the “luddite” faction has taken hold instead of recognizing other professionals strengths and allowing those tasks be delegated so as to allow more time for Dr./patient care.

Enjoying your insights, this blog is a keeper!

SR

I am an independent Psych Nurse Practitioner as well as a Family Nurse Practitioner as well as a Licensed Professional Counselor, two years post-master’s doctoral training as a clinical psychologist; I have my own company, operate independently prescribing medications and providing counseling for complicated bipolar, schizoaffective/schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, substance abuse/dependence, etc. I did what the Psychiatrists do: I secured a fantastic residency learning from the psychiatrists as much as I could and continuing to learn through the Neuroscience Education Institute. I operate just like a Pyschiatrist–I know how I compare as I’ve watched Pyschiatrists do their thing with patients since the 1980’s as a mental health technician, counselor, family therapist on psychiatric units in Berkeley, California, Dallas, Texas. I sat in on their meetings with patients–I’ve watched probably 50 plus psychiatrists and most of them were struggling with connecting with the patients, compassionate care—they were medication management only–that was their training. When it came to psychotherapy it was clear this was their weakness. Of course, like any profession those that went on to get training in psychodynamic theory, etc. became adept–however most that I saw did not.

My point is–I am not an adjunct to care for the Psychiatrist–I am the care–I am not a midlevel–I am the Practitioner–the Psychiatrist-the counselor–I am an expert at psychotherapy as well as medication management of complicated psychopharmacology cases.

It all depends on the training, the residency and the additional training a Practitioner has. Some NP’s are not adept at therapy as their focus of training was medication management. Others didn’t have a great residency, others prefer to work with a Psychiatrist. Others like myself, have been in the field 25 years and did the training, the residency and continue to do the work to be independent of physicians and operate just like a Psychiatrist. One does not have to go to medical school to practice medicine. The proof is in the research, the clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction .

Let’s say I’m an affiliate for company X but I have no passion to promote this company and I actually despise it.

I personally highly recommend Perry Marshall’s Definitive Guide to Google Ad – Words (I am in no way affiliated with Perry Marshall).

Many of us remember the days of the HUGE networking parties

where you would go and talk with someone only long enough to receive their business cards.

Sounds like you want Psychiatry to go through nursing school! This is exactly the model of care we are taught from day 1. Franklin Holcomb, DNP, APRN, PMHNP-BC, CARN-AP