The practice of medicine has changed enormously in just the last few years. While the upcoming implementation of the Affordable Care Act promises even further—and more dramatic—change, one topic which has received little popular attention is the question of exactly who provides medical services. Throughout medicine, physicians (i.e., those with MD or DO degrees) are being replaced by others, whenever possible, in an attempt to cut costs and improve access to care.

The practice of medicine has changed enormously in just the last few years. While the upcoming implementation of the Affordable Care Act promises even further—and more dramatic—change, one topic which has received little popular attention is the question of exactly who provides medical services. Throughout medicine, physicians (i.e., those with MD or DO degrees) are being replaced by others, whenever possible, in an attempt to cut costs and improve access to care.

In psychiatry, non-physicians have long been a part of the treatment landscape. Most commonly today, psychiatrists focus on “medication management” while psychologists, psychotherapists, and others perform “talk therapy.” But even the med management jobs—the traditional domain of psychiatrists, with their extensive medical training—are gradually being transferred to other so-called “midlevel” providers.

The term “midlevel” (not always a popular term, by the way) refers to someone whose training lies “mid-way” between that of a physician and another provider (like a nurse, psychologist, social worker, etc) but who is still licensed to diagnose and treat patients. Midlevel providers usually work under the supervision (although often not direct) of a physician. In psychiatry, there are a number of such midlevel professionals, with designations like PMHNP, PMHCNS, RNP, and APRN, who have become increasingly involved in “med management” roles. This is partly because they tend to demand lower salaries and are reimbursed at a lower rate than medical professionals. However, many physicians—and not just in psychiatry, by the way—have grown increasingly defensive (and, at times, downright angry, if some physician-only online communities are any indication) about this encroachment of “lesser-trained” practitioners onto their turf.

In my own experience, I’ve worked side-by-side with a few RNPs. They performed their jobs quite competently. However, their competence speaks less to the depth of their knowledge (which was impressive, incidentally) and more to the changing nature of psychiatry. Indeed, psychiatry seems to have evolved to such a degree that the typical psychiatrist’s job—or “turf,” if you will—can be readily handled by someone with less (in some cases far less) training. When you consider that most psychiatric visits comprise a quick interview and the prescription of a drug, it’s no surprise that someone with even just a rudimentary understanding of psychopharmacology and a friendly demeanor can do well 99% of the time.

In my own experience, I’ve worked side-by-side with a few RNPs. They performed their jobs quite competently. However, their competence speaks less to the depth of their knowledge (which was impressive, incidentally) and more to the changing nature of psychiatry. Indeed, psychiatry seems to have evolved to such a degree that the typical psychiatrist’s job—or “turf,” if you will—can be readily handled by someone with less (in some cases far less) training. When you consider that most psychiatric visits comprise a quick interview and the prescription of a drug, it’s no surprise that someone with even just a rudimentary understanding of psychopharmacology and a friendly demeanor can do well 99% of the time.

This trend could spell (or hasten) the death of psychiatry. More importantly, however, it could present an opportunity for psychiatry’s leaders to redefine and reinvigorate our field.

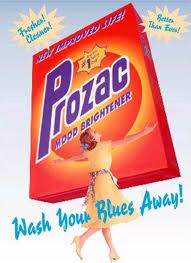

It’s easy to see how this trend could bring psychiatry to its knees. Third-party payers obviously want to keep costs low, and with the passage of the ACA the role of the third-party payer—and “treatment guidelines” that can be followed more or less blindly—will be even stronger. Patients, moreover, increasingly see psychiatry as a medication-oriented specialty, thanks to direct-to-consumer advertising and our medication-obsessed culture. Taken together, this means that psychiatrists might be passed over in favor of cheaper workers whose main task will be to follow guidelines or protocols. If so, most patients (unfortunately) wouldn’t even know the difference.

On the other hand, this trend could also present an opportunity for a revolution in psychiatry. The predictions in the previous paragraph are based on two assumptions: first, that psychiatric care requires medication, and second, that patients see the prescription of a drug as equivalent to a cure. Psychiatry’s current leadership and the pharmaceutical industry have successfully convinced us that these statements are true. But they need not be. Instead, they merely represent one treatment paradigm—a paradigm that, for ever-increasing numbers of people, leaves much to be desired.

On the other hand, this trend could also present an opportunity for a revolution in psychiatry. The predictions in the previous paragraph are based on two assumptions: first, that psychiatric care requires medication, and second, that patients see the prescription of a drug as equivalent to a cure. Psychiatry’s current leadership and the pharmaceutical industry have successfully convinced us that these statements are true. But they need not be. Instead, they merely represent one treatment paradigm—a paradigm that, for ever-increasing numbers of people, leaves much to be desired.

Preservation of psychiatry requires that psychiatrists find ways to differentiate themselves from midlevel providers in a meaningful fashion. Psychiatrists frequently claim that they are already different from other mental health practitioners, because they have gone to medical school and, therefore, are “real doctors.” But this is a specious (and arrogant) argument. It doesn’t take a “real doctor” to do a psychiatric interview, to compare a patient’s complaints to what’s written in the DSM (or what’s in one’s own memory banks) and to prescribe medication according to a guideline or flowchart. Yet that’s what most psychiatric care is. Sure, there are those cases in which successful treatment requires tapping the physician’s knowledge of pathophysiology, internal medicine, or even infectious disease, but these are rare—not to mention the fact that most treatment settings don’t even allow the psychiatrist to investigate these dimensions.

Thus, the sad reality is that today’s psychiatrists practice a type of medical “science” that others can grasp without four years of medical school and four years of psychiatric residency training. So how, then, can psychiatrists provide something different—particularly when appointment lengths continue to dwindle and costs continue to rise? To me, one answer is to revamp specialty training. I received my training in two institutions with very different cultures and patient populations. But both shared a common emphasis on teaching medication management. Did I need four years to learn how to prescribe drugs? No. In reality, practical psychopharmacology can be learned in a one-year (maybe even six-month) course—not to mention the fact that the most valuable knowledge comes from years of experience, something that only real life (and not a training program) can provide.

Beyond psychopharmacology, psychiatry training programs need to beef up psychotherapy training, something that experts have encouraged for years. But it goes further than that: psychiatry trainees need hands-on experience in the recovery model, community resources and their delivery, addictive illness and recovery concepts, behavioral therapies, case management, and, yes, how to truly integrate medical care into psychiatry. Furthermore, it wouldn’t hurt to give psychiatrists lessons in communication and critical thinking skills, cognitive psychology principles, cultural sensitivity, economics, business management, alternative medicine (much of which is “alternative” only because the mainstream says so), and, my own pet peeve, greater exposure to the wide, natural variability among human beings in their intellectual, emotional, behavioral, perceptual, and physical characteristics and aptitudes—so we stop labeling everyone who walks in the door as “abnormal.”

Beyond psychopharmacology, psychiatry training programs need to beef up psychotherapy training, something that experts have encouraged for years. But it goes further than that: psychiatry trainees need hands-on experience in the recovery model, community resources and their delivery, addictive illness and recovery concepts, behavioral therapies, case management, and, yes, how to truly integrate medical care into psychiatry. Furthermore, it wouldn’t hurt to give psychiatrists lessons in communication and critical thinking skills, cognitive psychology principles, cultural sensitivity, economics, business management, alternative medicine (much of which is “alternative” only because the mainstream says so), and, my own pet peeve, greater exposure to the wide, natural variability among human beings in their intellectual, emotional, behavioral, perceptual, and physical characteristics and aptitudes—so we stop labeling everyone who walks in the door as “abnormal.”

One might argue, that sounds great but psychiatrists don’t get paid for those things. True, we don’t. At least not yet. Nevertheless, a comprehensive approach to human wellness, taken by someone who has invested many years learning how to integrate these perspectives, is, in the long run, far more efficient than the current paradigm of discontinuous care, in which one person manages meds, another person provides therapy, another person serves as a case manager—roles which can change abruptly due to systemic constraints and turnover.

If we psychiatrists want to defend our “turf,” we can start by reclaiming some of the turf we’ve given away to others. But more importantly, we must also identify new turf and make it our own—not to provide duplicate, wasteful care, but instead to create a new treatment paradigm in which the focus is on the patient and the context in which he or she presents, and treatment involves only what is necessary (and which is likely to work for that particular individual). Only a professional with a well-rounded background can bring this paradigm to light, and psychiatrists—those who have invested the time, effort, expense, and hard work to devote their lives to the understanding and treatment of mental illness—are uniquely positioned to bring this perspective to the table and make it happen.

Posted by stevebMD

Posted by stevebMD