I know I write a lot about my disillusionment with modern psychiatry. I have lamented the overriding psychopharmacological imperative, the emphasis on rapid diagnosis and medication management, at the expense of understanding the whole patient and developing truly “personalized” treatments. But at the risk of sounding like even more of a heretic, I’ve noticed that not only do psychopharmacologists really believe in what they’re doing, but they often believe it even in the face of evidence to the contrary.

I know I write a lot about my disillusionment with modern psychiatry. I have lamented the overriding psychopharmacological imperative, the emphasis on rapid diagnosis and medication management, at the expense of understanding the whole patient and developing truly “personalized” treatments. But at the risk of sounding like even more of a heretic, I’ve noticed that not only do psychopharmacologists really believe in what they’re doing, but they often believe it even in the face of evidence to the contrary.

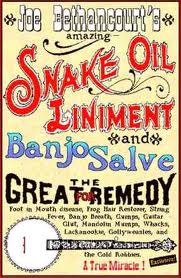

It all makes me wonder whether we’re practicing a sort of pseudoscience.

For those of you unfamiliar with the term, check out Wikipedia, which defines “pseudoscience” as: “a claim, belief, or practice which is presented as scientific, but which does not adhere to a valid scientific method, lacks supporting evidence or plausibility, cannot be reliably tested…. [is] often characterized by the use of vague, exaggerated or unprovable claims [and] an over-reliance on confirmation rather than rigorous attempts at refutation…”

Among the medical-scientific community (of which I am a part, by virtue of my training), the label of “pseudoscience” is often reserved for practices like acupuncture, naturopathy, and chiropractic. Each may have its own adherents, its own scientific language or approach, and even its own curative power, but taken as a whole, their claims are frequently “vague or exaggerated,” and they fail to generate hypotheses which can then be proven or (even better) refuted in an attempt to refine disease models.

Among the medical-scientific community (of which I am a part, by virtue of my training), the label of “pseudoscience” is often reserved for practices like acupuncture, naturopathy, and chiropractic. Each may have its own adherents, its own scientific language or approach, and even its own curative power, but taken as a whole, their claims are frequently “vague or exaggerated,” and they fail to generate hypotheses which can then be proven or (even better) refuted in an attempt to refine disease models.

Does clinical psychopharmacology fit in the same category?

Before going further, I should emphasize I’m referring to clinical psychopharmacology: namely, the practice of prescribing medications (or combinations thereof) to actual patients, in an attempt to treat illness. I’m not referring to the type of psychopharmacology practiced in research laboratories or even in clinical research settings, where there is an accepted scientific method, and an attempt to test hypotheses (even though some premises, like DSM diagnoses or biological mechanisms, may be erroneous) according to established scientific principles.

The scientific method consists of: (1) observing a phenomenon; (2) developing a hypothesis; (3) making a prediction based on that hypothesis; (4) collecting data to attempt to refute that hypothesis; and (5) determining whether the hypothesis is supported or not, based on the data collected.

In psychiatry, we are not very good at this. Sure, we may ask questions and listen to our patients’ answers (“observation”), come up with a diagnosis (a “hypothesis”) and a treatment plan (a “prediction”), and evaluate our patients’ response to medications (“data collection”). But is this only a charade?

First of all, the diagnoses we give are not based on a valid understanding of disease. As the current controversy over DSM-5 demonstrates, even experts find it hard to agree on what they’re describing. Maybe if we viewed DSM diagnoses as “suggestions” or “prototypes” rather than concrete diagnoses, we’d be better off. But clinical psychopharmacology does the exact opposite: it puts far too much emphasis on the diagnosis, which predicts the treatment, when in fact a diagnosis does not necessarily reflect biological reality but rather a “best guess.” It’s subject to change at any time, as are the fluctuating symptoms that real patients present with. (Will biomarkers help? I’m not holding my breath.)

First of all, the diagnoses we give are not based on a valid understanding of disease. As the current controversy over DSM-5 demonstrates, even experts find it hard to agree on what they’re describing. Maybe if we viewed DSM diagnoses as “suggestions” or “prototypes” rather than concrete diagnoses, we’d be better off. But clinical psychopharmacology does the exact opposite: it puts far too much emphasis on the diagnosis, which predicts the treatment, when in fact a diagnosis does not necessarily reflect biological reality but rather a “best guess.” It’s subject to change at any time, as are the fluctuating symptoms that real patients present with. (Will biomarkers help? I’m not holding my breath.)

Second, our predictions (i.e., the medications we choose for our patients) are always based on assumptions that have never been proven. What do I mean by this? Well, we have “animal models” of depression and theories of errant dopamine pathways in schizophrenia, but for “real world” patients—the patients in our offices—if you truly listen to what they say, the diagnosis is rarely clear. Instead, we try to “make the patients fit the diagnosis” (which becomes easier to do as appointment lengths shorten), and then concoct treatment plans which perfectly fit the biochemical pathways that our textbooks, drug reps, and anointed leaders lay out for us, but which may have absolutely nothing to do with what’s really happening in the bodies and minds of our patients.

Finally, the whole idea of falsifiability is absent in clinical psychopharmacology. If I prescribe an antidepressant or even an anxiolytic or sedative drug to my patient, and he returns two weeks later saying that he “feels much better” (or is “less anxious” or is “sleeping better”), how do I know it was the medication? Unless all other variables are held strictly constant—which is impossible to do even in a well-designed placebo-controlled trial, much less the real world—I can make no assumption about the effect of the drug in my patient’s body.

It gets even more absurd when one listens to a so-called “expert psychopharmacologist,” who uses complicated combinations of 4, 5, or 6 medications at a time to achieve “just the right response,” or who constantly tweaks medication doses to address a specific issue or complaint (e.g., acne, thinning hair, frequent cough, yawning, etc, etc), using sophisticated-sounding pathways or models that have not been proven to play a role in the symptom under consideration. Even if it’s complete guesswork (which it often is), the patient may improve 33% of the time (“Success! My explanation was right!”), get worse 33% of the time (“I didn’t increase the dose quite enough!”), and stay the same 33% of the time (“Are any other symptoms bothering you?”).

It gets even more absurd when one listens to a so-called “expert psychopharmacologist,” who uses complicated combinations of 4, 5, or 6 medications at a time to achieve “just the right response,” or who constantly tweaks medication doses to address a specific issue or complaint (e.g., acne, thinning hair, frequent cough, yawning, etc, etc), using sophisticated-sounding pathways or models that have not been proven to play a role in the symptom under consideration. Even if it’s complete guesswork (which it often is), the patient may improve 33% of the time (“Success! My explanation was right!”), get worse 33% of the time (“I didn’t increase the dose quite enough!”), and stay the same 33% of the time (“Are any other symptoms bothering you?”).

Of course, if you’re paying good money to see an “expert psychopharmacologist,” who has diplomas on her wall and who explains complicated neurochemical pathways to you using big words and colorful pictures of the brain, you’ve already increased your odds of being in the first 33%. And this is the main reason psychopharmacology is acceptable to most patients: not only does our society value the biological explanation, but psychopharmacology is practiced by people who sound so intelligent and … well, rational. Even though the mind is still a relatively impenetrable black box and no two patients are alike in how they experience the world. In other words, psychopharmacology has capitalized on the placebo response (and the ignorance & faith of patients) to its benefit.

Psychopharmacology is not always bad. Sometimes psychotropic medication can work wonders, and often very simple interventions provide patients with the support they need to learn new skills (or, in rare cases, to stay alive). In other words, it is still a worthwhile endeavor, but our expectations and our beliefs unfortunately grow faster than the evidence base to support them.

Psychopharmacology is not always bad. Sometimes psychotropic medication can work wonders, and often very simple interventions provide patients with the support they need to learn new skills (or, in rare cases, to stay alive). In other words, it is still a worthwhile endeavor, but our expectations and our beliefs unfortunately grow faster than the evidence base to support them.

Similarly, “pseudoscience” can give results. It can heal, too: some health-care plans willingly pay for acupuncture, and some patients swear by Ayurvedic medicine or Reiki. And who knows, there might still be a valid scientific basis for the benefits professed by advocates of these practices.

In the end, though, we need to stand back and remind ourselves what we don’t know. Particuarly at a time when clinical psychopharmacology has come to dominate the national psyche—and command a significant portion of the nation’s enormous health care budget—we need to be extra critical and ask for more persuasive evidence of its successes. And we should not bring to the mainstream something that might more legitimately belong in the fringe.

Posted by stevebMD

Posted by stevebMD