What impact can psychiatry have on the health of a community?

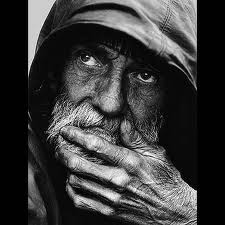

For three years, I have worked part-time in a non-profit psychopharmacology clinic, treating a wide range of individuals from a poor, underserved urban area. In a recent post, I wrote that many of the complaints endorsed by patients from this population may be perceived as symptoms of a mental illness. At one point or another (if not chronically), people complain of “anxiety,” “depression,” “insomnia,” “hopelessness,” etc.—even if these complaints simply reflect their response to environmental stressors, and not an underlying mental illness.

For three years, I have worked part-time in a non-profit psychopharmacology clinic, treating a wide range of individuals from a poor, underserved urban area. In a recent post, I wrote that many of the complaints endorsed by patients from this population may be perceived as symptoms of a mental illness. At one point or another (if not chronically), people complain of “anxiety,” “depression,” “insomnia,” “hopelessness,” etc.—even if these complaints simply reflect their response to environmental stressors, and not an underlying mental illness.

However, because diagnostic criteria are so nonspecific, these complaints can easily lead to a psychiatric diagnosis, especially when the diagnostic evaluation is limited to a self-report questionnaire and a 15- or 20-minute intake appointment.

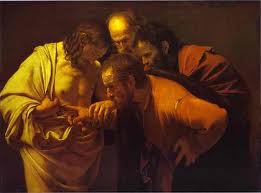

Personally, I struggle with two opposing biases: On the one hand, I want to believe that mental illness is a discrete entity, a pathological deviation from “normal,” and presents differently (longer duration, greater intensity, etc) from one’s expected reaction to a situation, however distressing that situation may be. On the other hand, if I take people’s complaints literally, everyone who walks into my office can be diagnosed as mentally ill.

Where do we draw the line? The question is an important one. The obvious answer is to use clinical judgment and experience to distinguish “illness” from “health.” But this boundary is vague, even under ideal circumstances. It breaks down entirely when patients have complicated, confusing, chaotic histories (or can’t provide one) and our institutions are designed for the rapid diagnosis and treatment of symptoms rather than the whole person. As a result, patients may be given a diagnosis where a true disorder doesn’t exist.

Where do we draw the line? The question is an important one. The obvious answer is to use clinical judgment and experience to distinguish “illness” from “health.” But this boundary is vague, even under ideal circumstances. It breaks down entirely when patients have complicated, confusing, chaotic histories (or can’t provide one) and our institutions are designed for the rapid diagnosis and treatment of symptoms rather than the whole person. As a result, patients may be given a diagnosis where a true disorder doesn’t exist.

This isn’t always detrimental. Sometimes it gives patients access to interventions from which they truly benefit—even if it’s just a visit with a clinician every couple of months and an opportunity to talk. Often, however, our tendency to diagnose and to pathologize creates new problems, unintended diversions, and potentially dire consequences.

The first consequence is the overuse of powerful (and expensive) medications which, at best, may provide no advantage over a placebo and, at worst, may cause devastating side effects, not to mention extreme costs to our overburdened health care system. Because Medicaid and Medicare reimbursements are better for medication management than for other non-pharmacological interventions, “treatment” often consists of brief “med check” visits every one to six months, with little time for follow-up or exploring alternative approaches. I have observed colleagues seeing 30 or 40 patients in a day, sometimes prescribing multiple antipsychotics with little justification, frequently in combination with benzodiazepines or other sedatives, and asking for follow-up appointments at six-month intervals. How this is supposed to improve one’s health, I cannot fathom.

Second, overdiagnosis and overtreatment diverts resources from where they are truly needed. For instance, the number of patients who can access a mental health clinic like ours but who do not have a primary care physician is staggering. Moreover, patients with severe, persistent mental illness (and who might be a danger to themselves or others when not treated) often don’t have access to assertive, multidisciplinary treatment. Instead, we’re spending money on medications and office visits by large numbers of patients for whom diagnoses are inaccurate, and medications provide dubious benefit.

Second, overdiagnosis and overtreatment diverts resources from where they are truly needed. For instance, the number of patients who can access a mental health clinic like ours but who do not have a primary care physician is staggering. Moreover, patients with severe, persistent mental illness (and who might be a danger to themselves or others when not treated) often don’t have access to assertive, multidisciplinary treatment. Instead, we’re spending money on medications and office visits by large numbers of patients for whom diagnoses are inaccurate, and medications provide dubious benefit.

Third, this overdiagnosis results in a massive population of “disabled,” causing further strain on scarce resources. The increasing number of patients on disability due to mental illness has long been chronicled. Some argue that the disability is itself a consequence of medication. It is also possible that some people may abuse the system to obtain certain resources. More commonly, however, I believe that the failure of the system (i.e., we clinicians) to perform an adequate evaluation—and our inclination to jump to a diagnosis—has swollen the disability ranks to an unsustainably high level.

Finally—and perhaps most distressingly—is the false hope that a psychiatric diagnosis communicates to a patient. I believe it can be quite disempowering for a person to hear that his normal response to a situation which is admittedly dire represents a mental illness. A diagnosis may provide a transient sense of relief (or, at the very least, alleviate one’s guilt), but it also tells a person that he is powerless to change his situation, and that a medication can do it for him. Worse, it makes him dependent upon a “system” whose underlying motives aren’t necessarily in the interest of empowering the neediest, weakest members of our society. I agree with a quote in a recent BBC Health story that a lifetime on disability “means that many people lose their sense of self-worth, identity, and esteem.” Again, not what I set out to do as a psychiatrist.

With these consequences, why does the status quo persist? For any observer of the American health care system, the answer seems clear: vested interests, institutional inertia, a clear lack of creative thought. To make matters worse, none of the examples described above constitute malpractice; they are, rather, the standard of practice.

With these consequences, why does the status quo persist? For any observer of the American health care system, the answer seems clear: vested interests, institutional inertia, a clear lack of creative thought. To make matters worse, none of the examples described above constitute malpractice; they are, rather, the standard of practice.

As a lone clinician, I am powerless to reverse this trend. That’s not to say I haven’t tried. Unfortunately, my attempts to change the way we practice have been met with resistance at many levels: county mental health administrators who have not returned detailed letters and emails asking to discuss more cost-effective strategies for care; fellow clinicians who have looked with suspicion (if not derision) upon my suggestions to rethink our approach; and—most painfully to me—supervisors who have labeled me a bigot for wanting to deprive people of the diagnoses and medications our (largely minority) patients “need.”

The truth is, my goal is not to deprive anyone. Rather, it is to encourage, to motivate, and to empower. Diagnosing illness where it doesn’t exist, prescribing medications for convenience and expediency, and believing that we are “helping” simply because we have little else to offer, unfortunately do none of the above.

Posted by stevebMD

Posted by stevebMD