A lively discussion has emerged on the NEI Global blog and on Daniel Carlat’s psychiatry blog about a recent post by Stephen Stahl, NEI chairman, pop(ular) psychiatrist, and promoter of psychopharmaceuticals. The post pertains to the exodus of pharmaceutical companies from neuroscience research (something I’ve blogged about too), and the changing face of psychiatry in the process.

Dr Stahl’s post is subtitled “Be Careful What You Ask For… You Just Might Get It” and, as one might imagine, it reads as a scathing (some might say “ranting”) reaction against several of psychiatry’s detractors: the “anti-psychiatry” crowd, the recent rules restricting pharmaceutical marketing to doctors, and those who complain about Big Pharma funding medical education. He singles out Dr Carlat, in particular, as an antipsychiatrist, implying that Carlat believes mental illnesses are inventions of the drug industry, medications are “diabolical,” and drugs exist solely to enrich pharmaceutical companies. [Not quite Carlat’s point of view, as a careful reading of his book, his psychopharmacology newsletter, and, yes, his blog, would prove.]

Dr Stahl’s post is subtitled “Be Careful What You Ask For… You Just Might Get It” and, as one might imagine, it reads as a scathing (some might say “ranting”) reaction against several of psychiatry’s detractors: the “anti-psychiatry” crowd, the recent rules restricting pharmaceutical marketing to doctors, and those who complain about Big Pharma funding medical education. He singles out Dr Carlat, in particular, as an antipsychiatrist, implying that Carlat believes mental illnesses are inventions of the drug industry, medications are “diabolical,” and drugs exist solely to enrich pharmaceutical companies. [Not quite Carlat’s point of view, as a careful reading of his book, his psychopharmacology newsletter, and, yes, his blog, would prove.]

While I do not profess to have the credentials of Stahl or Carlat, I have expressed my own opinions on this matter in my blog, and wanted to enter my opinion on the NEI post.

With respect to Dr Stahl (and I do respect him immensely), I think he must re-evaluate his influence on our profession. It is huge, and not always in a productive way. Case in point: for the last two months I have worked in a teaching hospital, and I can say that Stahl is seen as something of a psychiatry “god.” He has an enormous wealth of knowledge, his writing is clear and persuasive, and the materials produced by NEI present difficult concepts in a clear way. Stahl’s books are directly quoted—unflinchingly—by students, residents, and faculty.

With respect to Dr Stahl (and I do respect him immensely), I think he must re-evaluate his influence on our profession. It is huge, and not always in a productive way. Case in point: for the last two months I have worked in a teaching hospital, and I can say that Stahl is seen as something of a psychiatry “god.” He has an enormous wealth of knowledge, his writing is clear and persuasive, and the materials produced by NEI present difficult concepts in a clear way. Stahl’s books are directly quoted—unflinchingly—by students, residents, and faculty.

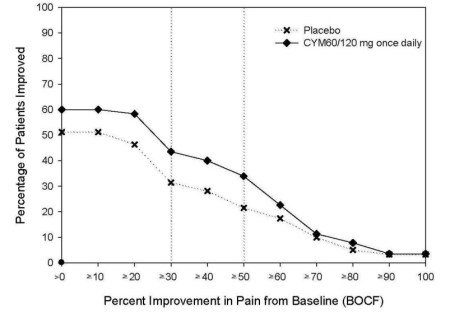

But there’s the rub. Stahl has done such a good job of presenting his (i.e., the psychopharmacology industry’s) view of things that it is rarely challenged or questioned. The “pathways” he suggests for depression, anxiety, psychosis, cognition, insomnia, obsessions, drug addiction, medication side effects—basically everything we treat in psychiatry—are accompanied by theoretical models for how some new pharmacological agent might (or will) affect these pathways, when in fact the underlying premises or the proposed drug mechanisms—or both—may be entirely wrong. (BTW, this is not a criticism of Stahl, this is simply a statement of fact; psychiatry as a neuroscience is decidedly still in its infancy.)

When you combine Stahl’s talent with his extensive relationships with drug companies, it makes for a potentially dangerous combination. To cite just two examples, Stahl has written articles (in widely distributed “throwaway” journals) making compelling arguments for the use of low-dose doxepin (Silenor) and L-methylfolate (Deplin) in insomnia and depression, respectively, when the actual data suggest that their generic (or OTC) equivalents are just as effective. Many similar Stahl productions are included as references or handouts in drug companies’ promotional materials or websites.

When you combine Stahl’s talent with his extensive relationships with drug companies, it makes for a potentially dangerous combination. To cite just two examples, Stahl has written articles (in widely distributed “throwaway” journals) making compelling arguments for the use of low-dose doxepin (Silenor) and L-methylfolate (Deplin) in insomnia and depression, respectively, when the actual data suggest that their generic (or OTC) equivalents are just as effective. Many similar Stahl productions are included as references or handouts in drug companies’ promotional materials or websites.

How can this be “dangerous”? Isn’t Stahl just making hypotheses and letting doctors decide what to do with them? Well, not really. In my experience, if Stahl says something, it’s no longer a hypothesis, it becomes the truth.

I can’t tell you how many times a student (or even a professor of mine) has explained to me “Well, Stahl says drug A works this way, so it will probably work for symptom B in patient C.” Unfortunately, we don’t have the follow-up discussion when drug A doesn’t treat symptom B; or patient C experiences some unexpected side effect (which was not predicted by Stahl’s model); or the patient improves in some way potentially unrelated to the medication. And when we don’t get the outcome we want, we invoke yet another Stahl pathway to explain it, or to justify the addition of another agent. And so on and so on, until something “works.” Hey, a broken clock is still correct twice a day.

I don’t begrudge Stahl for writing his articles and books; they’re very well written, and the colorful pictures are fun to look at– it makes psychiatry almost as easy as painting by numbers. I also (unlike Carlat) don’t get annoyed when doctors do speaking gigs to promote new drugs. (When these paid speakers are also responsible for teaching students in an academic setting, however, that’s another issue.) Furthermore, I accept the fact that drug companies will try to increase their profits by expanding market share and promoting their drugs aggressively to me (after all, they’re companies—what do we expect them to do??), or by showing “good will” by underwriting CME, as long as it’s independently confirmed to be without bias.

The problem, however, is that doctors often don’t ask for the data. We don’t ask whether Steve Stahl’s models might be wrong (or biased). We don’t look closely at what we’re presented (either in a CME lesson or by a drug rep) to see whether it’s free from commercial influence. And, perhaps most distressingly, we don’t listen enough to our patients to determine whether our medications actually do what Stahl tells us they’ll do.

The problem, however, is that doctors often don’t ask for the data. We don’t ask whether Steve Stahl’s models might be wrong (or biased). We don’t look closely at what we’re presented (either in a CME lesson or by a drug rep) to see whether it’s free from commercial influence. And, perhaps most distressingly, we don’t listen enough to our patients to determine whether our medications actually do what Stahl tells us they’ll do.

Furthermore, our ignorance is reinforced by a diagnostic tool (the DSM) which requires us to pigeonhole patients into a small number of diagnoses that may have no biological validity; a reimbursement system that encourages a knee-jerk treatment (usually a drug) for each such diagnosis; an FDA approval process that gives the illusion that diagnoses are homogeneous and that all patients will respond the same way; and only the most basic understanding of what causes mental illness. It creates the perfect opportunity for an authority like Stahl to come in and tell us what we need to know. (No wonder he’s a consultant for so many pharmaceutical companies.)

As Stahl writes, the departure of Big Pharma from neuroscience research is unfortunate, as our existing medications are FAR from perfect (despite Stahl’s texts making them sound pretty darn effective). However, this “breather” might allow us to pay more attention to our patients and think about what else—besides drugs—we can use to nurse them back to health. Moreover, refocusing our research efforts on the underlying psychology and biology of mental illness (i.e., research untainted by the need to show a clinical drug response or to get FDA approval) might open new avenues for future drug development.

As Stahl writes, the departure of Big Pharma from neuroscience research is unfortunate, as our existing medications are FAR from perfect (despite Stahl’s texts making them sound pretty darn effective). However, this “breather” might allow us to pay more attention to our patients and think about what else—besides drugs—we can use to nurse them back to health. Moreover, refocusing our research efforts on the underlying psychology and biology of mental illness (i.e., research untainted by the need to show a clinical drug response or to get FDA approval) might open new avenues for future drug development.

Stahl might be right that the anti-pharma pendulum has swung too far, but that doesn’t mean we can’t use this opportunity to make great strides forward in patient care. The paychecks of some docs might suffer. Hopefully our patients won’t.

Posted by stevebMD

Posted by stevebMD